Seriously, Read a Book!

Thoughts on books, often interpreted through the high-brow prism of cartoon (read: Archer) references. Wait! I had something for this...

Currently reading

The Highly Selective Dictionary for the Extraordinarily Literate

“Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes once declared, ‘Language is the skin of living thought.’ Just as your skin encloses your body, so does your vocabulary bound your mental life.”

I know! I know it seems to be the very apogee of absurdity for one to actually “read” a dictionary. But, Eugene Ehrlich has created a sort of paradoxical anti-dictionary; one to be considered “an antidote to the ongoing poisonous effects wrought by the forces of linguistic darkness.”

So, yes, I did, in fact, read all 192 pages of this lexicographic compendium (though not in one sitting). I'm sure I remain just as vulnerable to cacology* as ever (if not more so)—the same likely holds true for grandiloquence†.

Will I now be able to settle all logomachies‡? It's unlikely. Have I become a master of paronomasia§? Nay, I have not.

And yet, this newfound knowledge is not impracticable—a word I can now use with greater confidence thanks to Ehrlich's special attention to common solecisms**.

impracticable (im-PRAK-ti-ke-bel) adjective incapable of being put into practice. Do not confuse impracticable with impractical, which means unwise or not practical and is used most often to denote unrealistic behavior in the management of one's finances.

So, while it's rare for me to disagree with the author of my favorite dictionary (Ambrose Bierce's The Devil's Dictionary), I must say that this is a book that any logophile could love.

______________________________________________

* cacology (ke-KOL-e-jee) noun 1. bad choice of words. 2. poor pronunciation.

† grandiloquent (gran-DIL-e-kwent) adjective 1. using pompous language. 2. given to boastful talk.

‡ logomachy (loh-GOM-e-kee) noun, plural logomachies 1. a dispute about words. 2. a meaningless battle of words.

§ paronomasia (PAR-e-noh-MAY-zhe) noun 1. word play; punning. 2. a pun.

** solecism (SOL-e-SIZ-em) noun 1. a mistake in the use of language. 2. an offense against good manners or etiquette

2

2

2

2

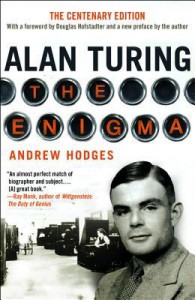

Alan Turing: The Enigma

Proximate Cause & Goodness of Fit

I'm not too proud to admit that the impetus for my picking up this biography was a trailer for the upcoming film on Alan Turing and his involvement with cracking the Enigma code during WWII (The Imitation Game). However, if you are interested exclusively (or even primarily) in the cryptanalytic exploits of Turing et al. at Bletchley Park then this is probably not — repeat not the Turing biography for you.

While Andrew Hodges thoroughly covers Turing's activities during the Second World War, this is just one piece of the whole. As one might expect of a book with an introduction by Douglas Hofstadter, it is an examination of both function and form. Alan's experiences were what they were because of who he was, and, in turn, these experiences made him into the man, the enigma he became.

The Young Turing Machine

Andrew Hodges, and Henrik Olesen, the artist behind "Some Illustrations to the Life of Alan Turing," both depict the young Alan Turing as a child inquisitive, and bright beyond his years. Alan, even in his earliest years, exhibited what Hodges refers to as a "desert island" mentality. If Alan had a problem, he relied on his own ingenuity to find an answer (e.g. inventing a machine to count gear revolutions and make adjustments as needed for his broken bicycle chain).

The young genius mind, however, outside of a vacuum, does not necessarily coalesce easily with the world around it. This was certainly true of Alan's early experiences in the English public school environment.* Alan was what some might refer to as "extremely pick-on-able." Thus, when he received a copy of Edwin Tenney Brewster's Natural Wonders Every Child Should Know on behalf of an unnamed benefactor in 1922, Alan was undoubtedly relieved to be able to escape into a world of science, numbers and natural order. Brewster portrayed the human body as a machine; one with duties, tasks, functions, and, perhaps more importantly, one that could be understood through the faculties of reason.

Obedience to Authority & The Imitation Game

In 1926, at the age of 13, Alan (left, below) was sent to the Sherborne School. With an emphasis good citizenship, and the individual's duty to fit into the system of their small society for the greater good (none of which included becoming a "man of science), Sherborne was not a good fit for Alan.

However, things began to turn around for Alan in 1928, when he met Christopher Morcom. Morcom, one year ahead of Alan at Sherburn and a member of a different "house," shared Alan's passion for science, maths, and exploration of the natural world. Unlike Alan, however, Morcom was able to integrate these interests with scholastic success.

The letters between Alan and Christopher during vacations from Sherborne are filled with an excited energy that comes with having someone with whom to share new discoveries. Christopher was both Alan's mentor and, as portrayed by Hodges, his first love. It's not clear whether this intimacy between the two was physical in nature, but the magnitude of Christopher's place in Alan's heart was made acutely and painfully clear when Christopher died suddenly of bovine tuberculosis in 1930.

The letters between Christopher Morcom's mother and Alan (a correspondence that continued for many years) reflect their shared grief in losing Christopher. The experience changed Alan in many ways, including a renewed dedication to honoring Christopher's memory by pursuing the interests they had shared (which, despite their youth, had included quantum physics, and Einstein's Relativity: The Special and the General Theory).

An Ordinary English Homosexual Atheist Mathematician

Though, unlike Christopher, Alan did not win a scholarship to his first choice, Trinity, he was admitted and matriculated to King's College, Cambridge in 1931. Though Alan remained secluded at King's, he was well-suited to its norms. In addition to the academic caliber of his professors and classmates, it was a socially and politically liberal environment; and it was in this context, that Alan became somewhat matter-of-factly open in his homosexuality.

Not knowing much about Cambridge (or really any university) in the 1940s, I was not clear as to whether Hodges' references to the life of an "ordinary english homosexual..." were made in jest. However, though Hodges is clear that this was not an easy life, it seems that it was much easier in the context of King's College.

Decidability, Computability & the Entscheidungsproblem

It is because of my own descriptive shortcomings that I won't be saying much about the content of the foundational problems (and paradoxes) in math and logic being asked and addressed by Turing and his contemporaries in the 1920s and 1930s. Suffice it to say that if you're operating under the impression that any system of mathematical logic can be complete, consistent and decidable, you might want to take a gander at some of Kurt Gödel's early work, and Turing's On Computable Numbers (though some might direct you toward the papers of Alonzo Church).

Before you say, 'well who cares?' Let it be known that the very notion of "computability" (in a time when what was meant by "computer" is akin to what we think of as a "writer" - one doing the writing/one doing the computing). Furthermore, this was the point at which Turing made a huge leap in the conceptual connection between abstract symbols and the physical world.

Like Schrödinger's cat, the Universal Turing Machine was a thought experiment, the elegance of which lies in its simplicity. Turing's conception (based on the idea of a typewriter) is that there is a machine that has a tape, which is divided into squares. Each square can bear a symbol. At a any given moment, one square is "in the machine," this is the scanned square, and it bears the scanned symbol.

Doesn't sound like much, I know, but here's the thing: the state of the machine (with its finite table of actions) can be determined by a singly expression using the symbols (which can be limited to two)...and there's recursion. It makes more sense if you read it from the experts!

To Oz and Back

It's the mid-1930s at this point, and Princeton is a pretty happening place. Turing, offered a fellowship there, crossed the pond to work with John von Neumann (who Hodges likens to the Wizard of Oz). Things just didn't work out as planned. Princeton was the height of wealth and aristocratic excess from Turing's point of view, and Turing was proving again the difference between having brilliant ideas and impressing them on the world.

However, Turing did have a good time at Princeton when taking part in "treasure hunts" consisting of series of encrypted clues. So, when Turing turned down a position at Princeton, and went back to Cambridge in 1938, his experiences stateside came in handy.

The Enigma & Bletchley Park

Prior to Britain's declaration of war, Alan Turing was (surprisingly) the first and only mathematician recruited to work at the super secret Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), and later moved to the cryptanalytic HQ at Bletchley Park. Alan, who had long dreamed of a chess-playing machine, suddenly had a practical problem for his obsession.

“Before the war my work was in logic and my hobby was cryptanalysis, and now it is the other way round.”

How so? Well, von Neumann's theory of ‘minimax’ strategies (the application of probabilities to any game between two players such that one chooses the “least bad” option) — one of making decisions in the absence of perfect information, had direct applications in strategic combat.

And, of course there was decryption of Enigma messages to be done. Alan's ability (and desire) to bridge the gap between mathematics and engineering was, for the first time, seen by others as an asset. Turing's thought experiments were being translated into actual electronic machinery—the Bombe (below), and the Colossus.

To be clear, it was the Bombe that was used to crack the Enigma. However, the Colossus was the first computer that approached Turing's conception of "universality" in that it was programmable. Many of those working at Bletchley were Wrens (seen below with the Colossus), members of the Women's Royal Naval Service. For Turing this was his first contact with women, including Joan Clarke. The two were briefly engaged, but this was broken off in 1941 when Turing informed Clarke of his homosexuality.

The Heart in Exile

Turing had been afforded more freedom during the war than he, perhaps, realized at the time. At the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) Turing completed the design for an Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), but in the face of bureaucracy and departmental divisiveness, he had almost no control over its engineering and construction.

“Alan Turing might be Valiant-for-Truth, but even he had been led into the work of deception by science, and by sex into lying to the police.”

Outside of the cloistered world of Cambridge, England was not exactly gay-friendly (didn't Oscar Wilde get hard labor for that?). In "exile" in Manchester, our ordinary English homosexual atheist, when burgled by the friends of a young man he brought home, reported the larceny to the police. However, by engaging in such “sexual perversion,” Turing had placed himself outside of the protection of the law. Turing was sentenced not to prison, but chemical castration by estrogen injections.

America was no better (just ask Lou Reed—his parents sent him for electroshock therapy, and that was for bisexuality). Having decided that homosexuals presented a “security risk,” Turing was banned from the United States as a whole.

In a twisted, endless loop, intolerance for homosexuality put any homosexual at risk for blackmail, which, in turn, made homosexuals a security risk, thereby increasing the intolerance with which we began.

On June 8th, 1954 Alan Turing was found dead in his home, lying in his bed. The identified the cause as cyanide poisoning, and the post-mortem inquest easily ruled it a suicide. In his house they found a jar of potassium cyanide, and a jam jar of cyanide solution. Next to his bed was a half-eaten apple.

____________________________________________

* For those of you who, like myself, live west of the Atlantic, "public school" in Britain is pretty much the opposite of what it means here (basically, it's the equivalent of the American private/boarding school...although most of us don't spend 15 years there).

3

3

2

2

Baby Hater

I'm not what one might call a “baby person.” I'm not against the very existence of babies*, but they make me decidedly uncomfortable. There are some exceptions, but for the most part, I don't ‘do’ babies (see disambiguation of term below).

Our titular Baby Hater, however, has a different bone to pick with the infant crowd; namely, the fact that she can't bear one. Infertile and alone, she has a decidedly grimmer view on the so-called circle of life.

After being forsaken by two assholes for clusters of cells that multiplied and multiplied and turned into wriggling shitting machines, so the wriggling shitting machines could grow up to be raised by the assholes, therefore destined to turn into assholes themselves, I grew to despise children.

And the children she so despises are constantly making themselves known. It seems parents these days just don't know how to keep their babies from crying.

So, what's to be done other than to start punching babies in the face? And boy does that turn out to be a rush! It also turns out that she's not alone in wanting to take these babies to task.

The book is only 37 pages long, so I'll leave it at that. It's funny, and dark, and ridiculous, and its cover bears an uncanny resemblance to Butters' grandmother from South Park (I'd take being punched in the face over “gummy bears” any day).

So, next time you miss your train because a parent thinks this is a good time to let little Suzy try out her walking skills on the escalator, maybe this will make for a relaxing read.

But, of course, every now and then a cool baby comes around (read: I'm always looking for an excuse to do a Wee Baby Seamus montage).

____________________________________________

* Unlike certain genre-defining country musicians who think all babies (those soft-skulled, fat little germ-sacks) should be drowned (well, not all babies, just baby people).

3

3

3

3

A Ticket to the Boneyard (Matthew Scudder #8)

Back when Matthew Scudder was still officially with the fuzz, he wasn’t exactly a stickler for the official rules. He did, however, have a set of his own, including the notion that if someone offers to buy you “a new hat,” you accept.* Officer Scudder wasn’t above keeping company with women in the oldest profession, and one in particular, Elaine.

Friends of Matt S. (since he’s working the steps, I’ll use the program’s preferred nomenclature) likely know from previous volumes, that Scudder-brand justice doesn’t always align with that of the American legal system. Both, however, have certain shortcomings. For Scudder, this may have included a little bit of staging in order to get a sadistic sociopath, John Motley, without compromising Elaine’s operation.

Motley may be confused about Matt’s role in this all, but that doesn’t stop him from seeking vengeance upon exit from the big house. And Motley is one scary dude. I don’t know if he was trained in Krav Maga or what, but Motley’s mitts are akin to those of a stevedore who lost his hand in a stevedoring accident and then got a hand transplant from an actual bear! Remind you of anyone?

I don’t know how, or why I strayed from my man Scudder for so long, but (shoutout to Peaches & Herb) being reunited feels so good.

____________________________________________

* For those of you out there still living Scudderless lives, this translates to roughly $25.

3

3

A Ticket to the Boneyard

Back when Matthew Scudder was still officially with the fuzz, he wasn’t exactly a stickler for the official rules. He did, however, have a set of his own, including the notion that if someone offers to buy you “a new hat,” you accept.* Officer Scudder wasn’t above keeping company with women in the oldest profession, and one in particular, Elaine.

Back when Matthew Scudder was still officially with the fuzz, he wasn’t exactly a stickler for the official rules. He did, however, have a set of his own, including the notion that if someone offers to buy you “a new hat,” you accept.* Officer Scudder wasn’t above keeping company with women in the oldest profession, and one in particular, Elaine. Friends of Matt S. (since he’s working the steps, I’ll use the program’s preferred nomenclature) likely know from previous volumes, that Scudder-brand justice doesn’t always align with that of the American legal system. Both, however, have certain shortcomings. For Scudder, this may have included a little bit of staging in order to get a sadistic sociopath, John Motley, without compromising Elaine’s operation.

Motley may be confused about Matt’s role in this all, but that doesn’t stop him from seeking vengeance upon exit from the big house. And Motley is one scary dude. I don’t know if he was trained in Krav Maga or what, but Motley’s mitts are akin to those of a stevedore who lost his hand in a stevedoring accident and then got a hand transplant from an actual bear! Remind you of anyone?

I don’t know how, or why I strayed from my man Scudder for so long, but (shoutout to Peaches & Herb) being reunited feels so good.

____________________________________________

* For those of you out there still living Scudderless lives, this translates to roughly $25.

Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Women Undercover in the Civil War

Four Civil War femme fatales? Yes, please!

This book is EVERYTHING!* It's like A League of Their Own had a lovechild with Shakespeare's Twelfth Night, and Doris Kearns Goodwin's (DKG) Team of Rivals, and seasoned it with an extra dash of siren song. (Or do you not season children?)

Actually, it's hard to dream up a single concoction to represent all that is contained in Karen Abbott's Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy. It is a unique breed of narrative non-fiction, with dialogue taken from primary sources (à la Eric Larson or DKG), but with a bit more literary leeway given (e.g. I can't imagine how one would garner access to the dying thoughts of a drowning woman and/or the extent to which a purse full of gold may have tugged at her neck). Additionally, the four women do not share a single story by any stretch of the imagination — a good thing if, like me, you enjoy "rotisserie-style" narration.**

Setting the Scene:

We open curtain around summertime 1861, which (and I hope you already know this) coincides with the American Civil War. Since any man worth his mettle is battlefield-bound (click the picture below, The Art of Inspiring Courage, for some of the means by which the lady-folk made sure of this), there are bound to be many changes in the women's world. While some members of the fairer sex were content to contribute to the war effort by darning socks, others went above and beyond the typical call of duty.

Belle Boyd:

Belle's name was the only one with which I was familiar prior to reading this book. If ever there comes a time when we all get to go back in time to slap a person of our choosing, Belle would be pretty high up on my list (though don't tell her that, she'd probably take it as a compliment).†

"Why pick on poor Belle?" you ask. Where do I begin? For one thing, I have an (admittedly ironic) disdain for women who hate other women, and boy did Belle ever begrudge fellow females. She was also a media/attention hound (see how i refrained from using the word whore? oops!) before it was even a thing. When she was finally tossed into Old Capitol Prison (after her sixth or seventh arrest), she was "insulted" by the lack of torment she received relative to Rose O'Neal Greenhow (who you'll meet soon enough).

I couldn't help but feel smug satisfaction when I read that Belle was rebuffed by a fellow inmate in her constant search for a man to marry. Also, she was super into General Stonewall Jackson — to a near pathological extent (some might call it John Hinkley-esque), she tried to blackmail Lincoln, and so many other things, but my blood pressure can't take any more contemplation of the self-proclaimed “Cleopatra of the Secession.”

Sarah Emma Edmonds:

Unlike a certain southern drama queen, Emma Edmonds was hoping not to be noticed for her participation in the war. Why? Well, it wasn't strictly legal for a woman to impersonate a man to join the ranks (though, Abbott speculates, that there may have been up to 400 women who did so). However, Emma, not usually one for lying and deception, felt that it was her god-given duty to help with the war effort in whatever way possible. And, thus, one Frank Flint Thompson enlisted with the 2nd Michigan Infantry.

"Frank" logged most of his time as a battlefield medic, known as a "field nurse" (which had no feminine connotation at the time). Her story has the trials that often come with being a woman playing a man, especially in context intense for all.

Edmonds/Thompson's role got even more gender-bending when she was sent undercover as a man pretending to be a woman across enemy lines in order to collect some intel. Her story takes many a turn that I consider spoiler-worthy, so do with that what you will.

Rose O'Neal Greenhow:

Remember the lady who was lucky enough to receive way more torment than the envious Belle Boyd while locked up in Old Colony Prison? That would be Rose. And, while I'm no fan of Rose's politics, I've gotta give it to her when it comes to spycraft. There are over 174 documents intercepted going to and from Greenhow (some in pretty impressive ciphers) in the National Archives.

Why so much fuss over Rose? Well, she was pretty good at her "job," which, after her recruiter/handler, Thomas Jordan, officially defected to the CSA and went off to war, was pretty much Spymistress of the Confederate Secret Service. And, arguably, it was her communication of Union intel to General P. G. T. Beauregard that sealed the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run.

Rose had access to important information as a Washington socialite, well versed in "flattering" information out of the city's political elites (and potentially paramours). So, soon enough, Detective Allan Pinkerton, head of the Union Intelligence Service, was building up a dossier of info on Rose's activities.

Rose Greenhow, like Belle Boyd, had the annoying habit of "unsexing" herself (as far as I'm concerned, if you're running a spy ring and packing heat, you're kind of fair game), and then whining about how unfair it was to subject a woman to such barbarous treatment.

Between referring to Unionists as "slaves of Lincoln...that abolition despot," and (pro-slavery as ever) describing seasickness as "..the greatest evil to which poor human nature can be subjected," my patience wore thin with Rose. Also, if you don't want your daughter, Little Rose, in prison, you should probably avoid using her as a spy.

Elizabeth Van Lew (and Mary Jane too):

Elizabeth Van Lew sacrificed what could have otherwise been a cushy life for her abolitionist beliefs. She emancipated her family's slaves (though some opted to stay as paid servants), and spent the bulk of her inheritance buying and freeing their relatives. Living in Richmond, hers was not a particularly popular position to take.

Like Rose Greenhow, Van Lew ran a sizable spy ring, but her real stroke of genius involved a collaboration between Elizabeth and her much beloved servant (for lack of a better word), Mary Bowser aka Mary Jane Richards. Having taught Mary Jane to read and write, referring to her as a “maid, of more than usual intelligence,” was quite the understatement. Mary Jane had an exceptional eidetic memory, which was what made her such an amazing asset "on the inside," when Van Lew "offered" Mary Jane to Varina Davis, First Lady of the CSA.

Parting words:

In an attempt to keep this review from becoming book-length, I'll stop here. If the subject(s) of this book are of interest to you, then I highly recommend it. I enjoyed the writing well enough, though it was hard to separate content from form. However, there aren't nearly enough books out there on kick-ass ladies in Civil War lore, so thanks, Karen Abbott, for that!

____________________________________________

* That's a thing kids say on the internet these days, right?

** Not a real term, but I can't think of a better way to describe the method of rotating among otherwise separate stories.

† I feel like a lot of people would want to take a swing at Hitler, and I really hate waiting in line.

1

1

2

2

The Man in the Rockefeller Suit: The Astonishing Rise and Spectacular Fall of a Serial Impostor

Not only did I read (well, technically listen to) this in one day, but practically in one sitting. It's the story of an absurdly audacious man – a criminal without conscience for whom I have no respect, but whose life/long con (one in the same, in many respects) intrigued me nonetheless. What can I say? I'm a sucker for true crime, and this one's a whopper.

Né (or should I say geboren?) Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter, the young German made his first American "contacts" while thumbing rides on the autobahn in hopes of escaping the perceived doldrums of his life in Bavaria. In 1978, the seventeen-year-old (photos below) made his way to the U.S. by writing in the name and address of a family he had hitched a ride with once, and set off for Berlin, Connecticut where he stayed with a family and enrolled as an exchange student at the local high school.

And let the lying begin! Christian, ever the chameleon, soon was affecting the absurd aristocratic accent of Thurston Howell III from Gilligan's Island, and voicing his distaste for the déclassé lifestyle of his host family as compared to his (completely fictional) charmed life in Germany as the son of a top-level "industrialist" at various impressive-sounding companies. He knew how to ingratiate himself well enough to get in the door, but also had a knack for wearing out his welcome.

His stint as a student in Wisconsin, "Chris Gerhart" nabbed himself a green card by way of a shotgun wedding, before he was on to bigger and better things. By the time he made his way to California (the wealthy community of San Marino, to be precise), Christopher Mountbatten Chichester (his pseudonym evolved with his persona) had taken his pedigree from coming from "money" to straight up royalty. He knew how to schmooze with the best of them, how to say the right things to the right people, how to get introduced around, all the while leveraging the credibility of newfound friends as his own.

He was also smart. Smart enough to be able to "talk shop" on a variety of subjects, and smart enough to give his stories the veneer of truth necessary to establish basic trust. His cover in California, however, got tricky when the son and daughter-in-law of the woman with whom he was staying (Jonathan and Linda Sohus) went MIA – though, for more on that you'll have to do some reading of your own.

Another move meant another name, so Christopher Chichester became Chris Crowe (third from the left, above) for his new life in Greenwich, CT. Of course there were signs (and certainly many that people can think of retrospect). Using the social security number of a David Berkowitz (aka the Son of Sam) probably sent up some red flags. His inability to actually do anything when he landed himself a job at a Wall Street firm raised enough concern to get him fired.

Here's the thing though: we (humans) do not like feeling that we've been duped. We justify bad decisions and misplaced trust more often than not. Mistakes Were Made (But Not By Me) illustrates some great examples, small and large, of how deeply ingrained this tendency is in all of us. And Clark Rockefeller (his given name circa 1994) capitalized on this in his courtship of and marriage to high-powered McKinsey exec Sandra Boss most of all.

"Rockefeller" made some serious miscalculations when it came to his treatment of new neighbors when he and Boss made a move to Cornish, New Hampshire. His finicky paranoia around security, his grand plans for home renovations that never seemed to come to fruition – these were things that seemed like quirky "he's a Rockefeller" attributes to some.

But a slight change in perspective can make a huge difference. People who he had crossed (e.g. a woman he refused to allow to photograph his house's garden for historical archives, a man whose building donation to the town Clark hijacked) thought it all too appropriate when he played the Roman God of War, Mars, in a local production.

Of course, to me, at this point I couldn't un-see the uncanny similarity between Rockefeller as Mars and Buster Bluth in The Creation of Adam.

When Boss finally decided it was time for a divorce, Rockefeller went for that ever-useful solution to all marriage problems – having a baby (note my sarcasm). This part of the story is complicated. Rockefeller was basically using his wife as a cash cow, and pushing her to work more and more. The pregnancy was not planned. Boss' heavy travel schedule wasn't ideal for new motherhood. Both, of course, were happy when their daughter Reigh aka "Snooks" was born, but Clark continued to strong arm his wife onto the road and out of their daughter's life.

The move to Boston (a minor concession to keep the marriage afloat) didn't change much. And, long of the short, if you recognize the girl above, it's probably due to the Amber Alert that went out when Rockefeller absconded with her in 2008. Though, as mug and courtroom photos (below) would suggest, he was captured days later.

My biggest criticism of this book was that it was a bit light on trial material. I, for one, did not finish this book feeling confused as to whether Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter was a delusional victim of mental illness, or a master manipulator. The conclusion wasn't forced upon me per se, but I'm pretty sure author Mark Seal would agree.

3.5/5 stars!

Three or four pages worth of interested in the story? Mark Seal's “The Man Who Played Rockefeller” adaptation for the Wall Street Journal is the place to go.

2

2

Faceless Killers (Kurt Wallander #1)

“To grow old is to live in fear. The dread of something menacing that you felt when you were a child returns when you get old.”

The first episode of a sitcom is usually a bit clunky. The joke to exposition ratio is low, and you’ve got all these new people to meet. While Henning Mankell’s Kurt Wallander series is by no stretch of the imagination a "situational comedy," I tried to give its first volume the same benefit of the doubt.

When our depressed, middle-aged police detective/protagonist, Kurt, mentally mused over his wife’s recent departure for the fourth time during my first 30 minutes of reading, I started to get worried. I didn’t expect things to be peppy; Scandinavian crime writing isn’t known for sunshine and rainbows. However, I didn’t want Wallander’s malaise to turn into my own.

I think Dan Schwent’s comment, “I liked it but it made me tired,” is pretty dead-on. The mystery itself, a "grisly" double homicide of an elderly couple which may or may not be connected to the growing refugee camp populations in rural Ystad (and throughout Sweden), wasn’t a thriller — and that’s ok. Sometimes I like moody, misanthropic reflections on society and its decline. But, while I would probably hate reading about my perfect proxy, I had some trouble relating to woes of Wallander’s world.

Side note: Between this book and Stieg Larsson’s trilogy, is anyone else getting concerned about the Swedish social service system? I mean, I know we don’t have a great thing going here in the U.S. of A. (see Dennis Lehane), but still…

8

8

4

4

NOS4A2

As I don't even like to be in the same room as the Nosferatu at my local movie monster wax museum (Nightmare Galley), it's probably a good thing that I somehow totally ignored the vanity plate wordplay for NOS4A2.

I'm pretty late to the game in reading my first Joe Hill, so I can't imagine I have much to add. However, I never pass up a chance to fangirl over Steve McQueen (and/or delicious motorcycles), and Hill has provided me with quite the slow pitch.

In my defense, the vehicular ogling isn't actually all that off-topic. This is a story in which special rides take you special places. The young Vic McQueen (whose last name alone had my envisioning favorite scenes from The Great Escape even before the Triumph entered the picture) had her Raleigh Tuff Burner to steer her to "the Shorter Way."

For Charlie Manx, 'twas the lifeblood of his 1938 Rolls Royce Wraith coursed through his veins en route to Christmasland.

And then, of course, there is the Triumph — a pre-1974 Bonnie, right-hand clutch and all. The Triumph Bonneville is so McQueen that Triumph did an SMQ edition T100 (which has been idling on my christmas list for far too long now).

While the Bonnie didn't log the silver screen stunt scenes for The Great Escape (that was a BMW costume-wearing '61 Trophy TR6), it managed to make some key cameos elsewhere.

Joe might not have my eyes for McQueen's musculature in this shot, but I'm pretty sure he'd be into the general awesomeness that is SMQ on a Triumph.

As for the book? It's a great ride all its own.

7

7

9

9

Alan Turing: The Enigma The Centenary Edition

Alan Turing 23 June, 1912 - 7 June, 1954

Alan Turing 23 June, 1912 - 7 June, 1954Proximate Cause & Goodness of Fit

I'm not too proud to admit that the impetus for my picking up this biography was a trailer for the upcoming film on Alan Turing and his involvement with cracking the Enigma code during WWII (The Imitation Game). However, if you are interested exclusively (or even primarily) in the cryptanalytic exploits of Turing et al. at Bletchley Park then this is probably not — repeat not the Turing book for you.

While Andrew Hodges thoroughly covers Turing's activities during the Second World War, this is just one piece of the whole. As one might expect of a book with an introduction by Douglas Hofstadter, it is an examination of both function and form. Alan's experiences were what they were because of who he was, and, in turn, these experiences made him into the man, the enigma he became.

The Young Turing Machine

Andrew Hodges, and Henrik Olesen, the artist behind "Some Illustrations to the Life of Alan Turing," both depict the young Alan Turing as a child inquisitive, and bright beyond his years. Alan, even in his earliest years, exhibited what Hodges refers to as a "desert island" mentality. If Alan had a problem, he relied on his own ingenuity to find an answer (e.g. inventing a machine to count gear revolutions and make adjustments as needed for his broken bicycle chain).

The young genius mind, however, outside of a vacuum, does not necessarily coalesce easily with the world around it. This was certainly true of Alan's early experiences in the English public school environment.* Alan was what some might refer to as "extremely pick-on-able." Thus, when he received a copy of Edwin Tenney Brewster's Natural Wonders Every Child Should Know on behalf of an unnamed benefactor in 1922, Alan was undoubtedly relieved to be able to escape into a world of science, numbers and natural order. Brewster portrayed the human body as a machine; one with duties, tasks, functions, and, perhaps more importantly, one that could be understood through the faculties of reason.

Obedience to Authority & The Imitation Game

In 1926, at the age of 13, Alan (left, below) was sent to the Sherborne School. With an emphasis good citizenship, and the individual's duty to fit into the system of their small society for the greater good (none of which included becoming a "man of science), Sherborne was not a good fit for Alan.

However, things began to turn around for Alan in 1928, when he met Christopher Morcom. Morcom, one year ahead of Alan at Sherburn and a member of a different "house," shared Alan's passion for science, maths, and exploration of the natural world. Unlike Alan, however, Morcom was able to integrate these interests with scholastic success.

The letters between Alan and Christopher during vacations from Sherborne are filled with an excited energy that comes with having someone with whom to share new discoveries. Christopher was both Alan's mentor and, as portrayed by Hodges, his first love. It's not clear whether this intimacy between the two was physical in nature, but the magnitude of Christopher's place in Alan's heart was made acutely and painfully clear when Christopher died suddenly of bovine tuberculosis in 1930.

The letters between Christopher Morcom's mother and Alan (a correspondence that continued for many years) reflect their shared grief in losing Christopher. The experience changed Alan in many ways, including a renewed dedication to honoring Christopher's memory by pursuing the interests they had shared (which, despite their youth, had included quantum physics, and Einstein's Relativity: The Special and the General Theory).

An Ordinary English Homosexual Atheist Mathematician

Though, unlike Christopher, Alan did not win a scholarship to his first choice, Trinity, he was admitted and matriculated to King's College, Cambridge in 1931. Though Alan remained secluded at King's, he was well-suited to its norms. In addition to the academic caliber of his professors and classmates, it was a socially and politically liberal environment; and it was in this context, that Alan became somewhat matter-of-factly open in his homosexuality.

Not knowing much about Cambridge (or really any university) in the 1940s, I was not clear as to whether Hodges' references to the life of an "ordinary english homosexual..." were made in jest. However, though Hodges is clear that this was not an easy life, it seems that it was much easier in the context of King's College.

Decidability, Computability & the Entscheidungsproblem

It is because of my own descriptive shortcomings that I won't be saying much about the content of the foundational problems (and paradoxes) in math and logic being asked and addressed by Turing and his contemporaries in the 1920s and 1930s. Suffice it to say that if you're operating under the impression that any system of mathematical logic can be complete, consistent and decidable, you might want to take a gander at some of Kurt Gödel's early work, and Turing's On Computable Numbers (though some might direct you toward the papers of Alonzo Church).

Before you say, ‘well who cares?’ Let it be known that the very notion of "computability" (in a time when what was meant by "computer" is akin to what we think of as a "writer" - one doing the writing/one doing the computing) was new. Furthermore, this was the point at which Turing made a huge leap in the conceptual connection between abstract symbols and the physical world.

Like Schrödinger's cat, the Universal Turing Machine was a thought experiment, the elegance of which lies in its simplicity. Turing's conception (based on the idea of a typewriter) is that there is a machine that has a tape, which is divided into squares. Each square can bear a symbol. At a any given moment, one square is "in the machine," this is the scanned square, and it bears the scanned symbol.

Doesn't sound like much, I know, but here's the thing: the state of the machine (with its finite table of actions) can be determined by a singly expression using the symbols (which can be limited to two)...and there's recursion. It makes more sense if you read it from the experts!

To Oz and Back

It's the mid-1930s at this point, and Princeton is a pretty happening place. Turing, offered a fellowship there, crossed the pond to work with John von Neumann (who Hodges likens to the Wizard of Oz). Things just didn't work out as planned. Princeton was the height of wealth and aristocratic excess from Turing's point of view, and Turing was proving again the difference between having brilliant ideas and impressing them on the world.

However, Turing did have a good time at Princeton when taking part in "treasure hunts" consisting of series of encrypted clues. So, when Turing turned down a position at Princeton, and went back to Cambridge in 1938, his experiences stateside came in handy.

The Enigma & Bletchley Park

Prior to Britain's declaration of war, Alan Turing was (surprisingly) the first and only mathematician recruited to work at the super secret Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), and later moved to the cryptanalytic HQ at Bletchley Park. Alan, who had long dreamed of a chess-playing machine, suddenly had a practical problem for his obsession.

How so? Well, von Neumann's theory of ‘minimax’ strategies (the application of probabilities to any game between two players such that one chooses the “least bad” option) — one of making decisions in the absence of perfect information, had direct applications in strategic combat.“Before the war my work was in logic and my hobby was cryptanalysis, and now it is the other way round.”

And, of course there was decryption of Enigma messages to be done. Alan's ability (and desire) to bridge the gap between mathematics and engineering was, for the first time, seen by others as an asset. Turing's thought experiments were being translated into actual electronic machinery—the Bombe (below), and the Colossus.

To be clear, it was the Bombe that was used to crack the Enigma. However, the Colossus was the first computer that approached Turing's conception of "universality" in that it was programmable. Many of those working at Bletchley were Wrens (seen below with the Colossus), members of the Women's Royal Naval Service. For Turing this was his first contact with women, including Joan Clarke. The two were briefly engaged, but this was broken off in 1941 when Turing informed Clarke of his homosexuality.

The Heart in Exile

Turing had been afforded more freedom during the war than he, perhaps, realized at the time. At the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) Turing completed the design for an Automatic Computing Engine (ACE), but in the face of bureaucracy and departmental divisiveness, he had almost no control over its engineering and construction.

Outside of the cloistered world of Cambridge, England was not exactly gay-friendly (didn't Oscar Wilde get hard labor for that?). In "exile" in Manchester, our ordinary English homosexual atheist, when burgled by the friends of a young man he brought home, reported the larceny to the police. However, by engaging in such “sexual perversion,” Turing had placed himself outside of the protection of the law. Turing was sentenced not to prison, but chemical castration by estrogen injections.“Alan Turing might be Valiant-for-Truth, but even he had been led into the work of deception by science, and by sex into lying to the police.”

America was no better (just ask Lou Reed—his parents sent him for electroshock therapy, and that was for bisexuality). Having decided that homosexuals presented a “security risk,” Turing was banned from the United States as a whole.

In a twisted, endless loop, intolerance for homosexuality put any homosexual at risk for blackmail, which, in turn, made homosexuals a security risk, thereby increasing the intolerance with which we began.

On June 8th, 1954 Alan Turing was found dead in his home, lying in his bed. The identified the cause as cyanide poisoning, and the post-mortem inquest easily ruled it a suicide. In his house they found a jar of potassium cyanide, and a jam jar of cyanide solution. Next to his bed was a half-eaten apple.

____________________________________________

* For those of you who, like myself, live west of the Atlantic, "public school" in Britain is pretty much the opposite of what it means here (basically, it's the equivalent of the American private/boarding school...although most of us don't spend 15 years there).

Scowler

Personal prolegomena:

This book fell into my mitts courtesy of another round of library roulette. About a quarter of the way in, things reached such a level of WTF that I broke one of my (made up) roulette rules, and just had to look it up to get a bead on this Scowler business.

Given the bit that I had just finished, I was surprised (at the very least) to find that it's actually classified as "young adult" and/or juvenile fiction. I'm relatively new to this "horror" business, but, still, really?!? That's not to say that a "young adult" couldn't handle it, but, nonetheless, this had me picturing "juveniles" à la Mary Ellen Mark's photograph, "Amanda And Her Cousin Amy."

Trudi's take will probably give you a better sense of things than I'll be offering here, but the gist involves a college-aged protagonist, Rye, who tends to the farm, his mother, and his younger sister, Sarah, in the wake of their (now imprisoned) menacing father, Marvin Burke. Things are not going well, the land is dried up, they've never recovered from whatever it is that Marvin did, and we know there's something involving "the unnamed three" looming over it all.

What, if anything, felt "young adult" to me about this book was the dearth of subtlety in foreshadowing. The book took me by surprise big time early on (if you've read it, then I'm guessing you know what I'm hinting at here)*, but after that I felt like the twists and turns were a bit too projected. On the flip side, I suppose that's how one builds suspense.

Cartoon connections:

For fans of South Park, the parallels with Cartman's trajectory in the 1% episode are pretty great (though, I'm guessing, unintentional).

___________________________________

* Fine, I'll spell it out for you:

(show spoiler)

4

4

4

4

4

4

2

2

Skinny Dip

Ok, now I get it! Of course, by "it" I mean all the Hiaasen hoopla among those with whom I share a certain brand of humor – an "it" that baffled me after my first encounter with Carl via Bad Monkey.

We're back in Florida, where even the craziest of characters are plausible probable. Since I'm not exactly trailblazing new territory here in book review land, I'll just give you some quick picks from the cast of Skinny Dip which may or may not overlap with everyone's favorite super secret spy agency (damn you terrorists for taking its name!):

Open scene with Joey Perrone tossed off a cruise ship and into the drink by her husband Chaz (who is selfish even by Sterling Archer standards).

But for his lack of ethical scruples, Chaz Perrone is ill-suited for his job as a biostitute (a clever portmanteau of biologist and prostitute). He's more than happy to fake results for his boss whose farming operations pollute the fragile ecosystem, but, he's not exactly outdoorsy.

Welcome to the Everglades, where everything either wants to eat you, or give you malaria.

Assorted other tie-ins?

Dumb muscle bodyguard (and one of the funniest characters).

We've also got the little old lady who breaks through even the toughest of façades.

Good times, good times.

5

5

Middlesex

Back in the era of the paper book (before people started furtively reading Fifty Shades of Grey and Mein Kampf* on their tablets and whatnot) there were certain books that you'd see everywhere; bedside tables, in this hands of fellow commuters, and staking out beach-chair territory.

Even in the digital era, there are books that it seems like everyone is reading. When this happens, I exhibit a distinct (albeit self-defeating) behavioral pattern wherein if I don't read it hot off the presses, I then feel all late to the game, can't decide when it's the right "moment" for me to pick it up and, thus, miss out on all the fun.†

For me, Middlesex fell prey to this cycle, so many thanks to Steve for suggesting I pick it up, because it was most definitely worth it. This book contains multitudes. It's a multi-generational epic (our narrator, Cal, invokes the muses), reminiscent of John Irving in that the passage of time shifts your focus as characters age, and cede the limelight to younger generations.

Middlesex certainly lends itself to the discussion of biological pre-determinism, the difference between gender and sex, and all sorts of topics pertaining to heteronormative cultural expectations. But, I just don't feel up to the task. Furthermore, I don't want to reduce the story arc to those standout frameworks. Cal reflects on his (as narrator he identifies as a male- so, go with it) own reticence to be an activist or icon, often leaning towards the path of least resistance (or avoidance) in his adult relationships.

"A word on my shame: I don't condone it."

Likewise, there is more to identity than gender and sexuality, and social stigma is bred from a variety of sources. This is a story of immigration, assimilation, wealth, race, inequality, generational disconnects, and the horrible, awkward, universal experience of adolescent becoming.

“The adolescent ego is a hazy thing, amorphous, cloud like. It wasn’t difficult to pour my identity into different vessels. In a sense, I was able to take whatever form was demanded of me.”

The book is not without faults, but flows in spite of certain clunky edifices. It even made me laugh a time or two – the Canada commentary toward the end was a favorite moment of the jingoistic elderly in rare form.

“But who knew what would happen once he got to Canada? Canada with its pacifism and its socialized medicine! Canada with its millions of French speakers! It was like…like…like a foreign country!”

__________________________________

* This is (depressingly) true. Hitler's Mein Kampf tops ebook download charts regularly (see article speculating as to the why here).

† I'm currently doing this with The Goldfinch, so someone make a note to remind me to get on that if haven't read it in a year or two.

8

8

The Song is You

Meet Gil "Hop"Hopkins — press man and all around fixer for "the nastiest, blackest-hearted team there is: Hollywood."

It was by chance (also known as the library wait list) that I landed myself back in late '40s tinsel town so soon after finishing The Black Dahlia. And the similarities don't end with location alone; as Hop chases down loose ends even the boys down at the local Hearst-owned rag office thought this sordid tale "might be Daughter of Black Dahlia." But, for Megan Abbott, I'd go almost anywhere.

The scene is set well, grime covered with layers of pancake makeup and the men upstairs running interference. For Hop, the search for some semblance of truth has tapped into something (Guilt? A conscience?) he thought he'd left behind long ago.

"Beneath the hard stare, the pancake, the waxy coat of lipstick, beneath that…hell, Hop had long ago stopped looking beneath that. Chances were too great that the underneath was worse."

And it is always so much worse...

Abbott does this breed of noir oh so well, but there was a certain feeling of intertwined closeness with the character, Hop in this case, that was lacking in comparison to the other two of hers (Dare Me, and Queenpin) I've read. I could speculate as to the gendered nature of this disconnect, but there are so many variables in the mix. In the end, my newfound love for Megan Abbott has landed her on a list of authors who I can only judge relative to their own greatness. So take this as three Megan Abbott-adjusted stars.

9

9

2

2

After the First Death

Alex Penn is having a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad day. He wakes up painfully hungover, coming out of a blackout drunk. When he finally gets out of bed, he discovers his clothes are all messed up, covered in blood it would seem and, just when he thinks things might have been looking up ( not having a nosebleed counts as a win in these circumstances), he turns his head. In what I assume is an homage to the words of Julius Caesar: "I looked, I saw, I vomited."

Sorry Alexander, Penn's got you trumped now, because you, my ginger little friend, did not wake up with a bloodied, dead hooker.* (See clarification re. terminology below). Oh, and did I mention Alex Penn was fresh out of prison on a Supreme Court ruling technicality? Also, he was in prison in the first place for (you guessed it!) killing a hooker.

More bad news for Mr. Penn, the fact that you have no memory of the crime in either case courtesy of voluntary intoxication doesn't get you off in the mens rea department (especially since we're in 1940s New York, and there's not much case law for you to run with). So what’s a fella’ to do?

This wasn't Scudder-level Block for me. I tend not to be big on reading about junkies (though Alex is not one himself) - too much talk of needle marks and being "on the nod" makes my stomach lurch. But, as always, Lawrence Block is a master of the grimy noir ambiance that gets richer in his later work.

_________________________________________

* Terminology clarification and life wisdom courtesy of one Sterling Archer:

5

5

2

2